Imagine a sculptor shaping a block of marble. The marble contains endless possible shapes, but the sculptor’s hands decide what emerges. Feature engineering works much the same way. Data is the raw marble. Algorithms are the tools. But it is the human, with their assumptions and preferences, who chips away to reveal what the model learns and ultimately believes. When biases shape these decisions, the model’s reality reflects not the world as it is, but the world as someone thought it should be. This subtle yet powerful influence is often overlooked. Just like learners in a data science course in Pune begin by framing the problem, the framing already carries a direction, an angle, and sometimes an unintended skew.

The Invisible Hand of Human Judgment

Before any model learns from data, someone decides what data matters. Which columns to keep. Which interactions to highlight. Which anomalies to remove. This stage feels technical, but it is full of personal judgment.

Feature engineering is the act of storytelling with numbers. Because of this, the data scientist’s worldview quietly shapes the narrative. Suppose we are forecasting employee churn. If we assume long hours are the main cause, we may emphasize time-tracking data, overlooking organizational culture, manager behavior, or geographic norms. The model ends up telling a narrowed story because its inputs were narrowed first.

This is similar to selecting only certain pieces of a puzzle, then blaming the puzzle for having holes. The model is not biased on its own. It merely learns what it was shown.

Choosing What to See: Selection Bias in Features

A common bias in feature engineering arises when selecting which variables to include. Humans tend to pick features that are available, familiar, or easy to measure. But what is easy to measure is not always what is meaningful. For example, a company trying to predict product demand may rely heavily on past sales data simply because it is neatly recorded. Yet customer sentiment, weather conditions, and competitor launches may influence demand even more.

The mind loves convenience. We trust what is already in front of us. This is selection bias in action.

This is even more pronounced in time-sensitive environments where teams rush to deploy models. Under pressure, people choose the obvious features, skipping the questions that require deeper inquiry. The result is a model that reinforces existing assumptions rather than discovering new truths.

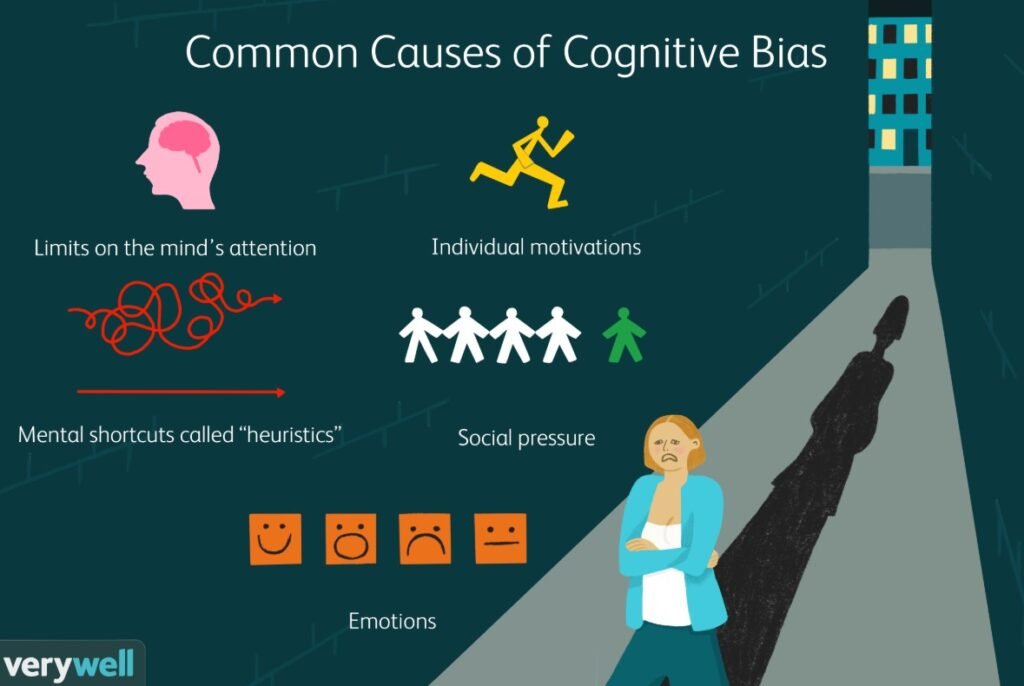

The Echoes of Past Experience: Anchoring and Confirmation

Anchoring is when a decision becomes centered around the first idea introduced. In feature engineering, this often appears when previous analyses influence new ones. If past models used income brackets as the primary predictor for credit scoring, future analysts may automatically lean toward income again, even if financial stability has shifted to depend more on savings behavior or spending consistency.

Confirmation bias strengthens this effect. Once an analyst has a hypothesis, the instinct is to find features that validate it, not challenge it. For example, if one believes that customers with high engagement on mobile apps are more loyal, they might emphasize mobile session duration, scroll depth, and click speed, ignoring offline or call-center interactions that may reveal dissatisfaction.

Models shaped under confirmation bias tend to predict what people already believe. They rarely uncover surprises.

Cultural and Contextual Shadows in Data

Data is not just numerical. It is cultural. Consider how communication style varies across regions. Direct feedback may signal dissatisfaction in one place but trust in another. If a model interprets tone or word choice without understanding culture, the features will misrepresent the reality being modeled.

Even geographic or socioeconomic assumptions can embed bias. Categorizing neighborhoods into “high value” and “low value” based on historic pricing ignores the fact that these prices reflect past inequalities. If used as features, such divisions risk perpetuating old disadvantages.

Models trained on biased features do not just repeat patterns. They calcify them.

Building Guardrails: Practices for Reducing Bias

Reducing bias in feature engineering does not mean eliminating human involvement. It means adding reflection, diversity, and iteration to the process.

- Cross-functional review: Bring domain experts, ethicists, and users to review features before modeling.

- Bias-check journaling: Document assumptions behind every feature choice to make invisible reasoning visible.

- Multiple perspectives: Encourage team members to propose alternative feature sets and compare outcomes.

- Monitor drift: Continuous evaluation ensures that a model’s representation of reality does not become outdated or skewed over time.

These practices help uncover blind spots, especially when teams are trained to be aware of how perspective shapes reasoning, as taught in a structured data science course in Pune.

Conclusion

Feature engineering is not just a technical exercise. It is the shaping of meaning. The features chosen determine what the model notices, what it ignores, and ultimately what it believes to be true. Cognitive biases are not flaws in intelligence, but natural patterns in human judgment. The key is not to eliminate them, but to understand and guide them.

When teams reflect on how they choose and craft features, they give their models the chance to see the world more clearly. And when models can see clearly, the insights they provide are not only more accurate, but more humane, fair, and wise.